Related Articles

Book Review

18th December 2025

2025 Butterfly Review

18th December 2025

Book Review - In Pursuit of Butterflies

11th February 2026

2025 Review

31st January 2026

Book Review - Western European Butterflies

Butterflies of Britain and Western Europe and Their Caterpillars: An Identification Guide

Author: Jean-Pierre Moussus

ISBN: 978-0-691-27179-8

Publisher: Princeton

Price: £27.95

Don't skip the introduction!

There's a tendency with a new identification guide to skip the introductory chapters and cut to the chase but that would be a mistake here for two reasons. Firstly, the introduction explains why particular species have been included and others left out, and it provides a well written account of how the butterfly fauna of Europe has been shaped by geography and the influence of glaciation. Secondly, it provides an analysis of the major threats to European butterflies and compares the situation in different countries. While we're familiar with the declines in butterfly numbers in the UK, the situation is even worse in some parts of northern Europe with, for example, the Netherlands showing a 15% loss of historical breeding species. While climate change is a factor in the decline of some species, the author argues that habitat degradation resulting from human activities is the most important cause and this, in his view, means that the situation is not hopeless. The right measures, enabling our agricultural land to become more compatible with biodiversity and linking habitats to help species disperse, will aid conservation at a landscape scale. Moussus does not under-estimate this task but hopes that disseminating the information in the guide will improve understanding of the challenges ahead. In short, conservation is based on sound identification of species and a consequent knowledge of their distribution: he puts forward a series of keys to achieve this.

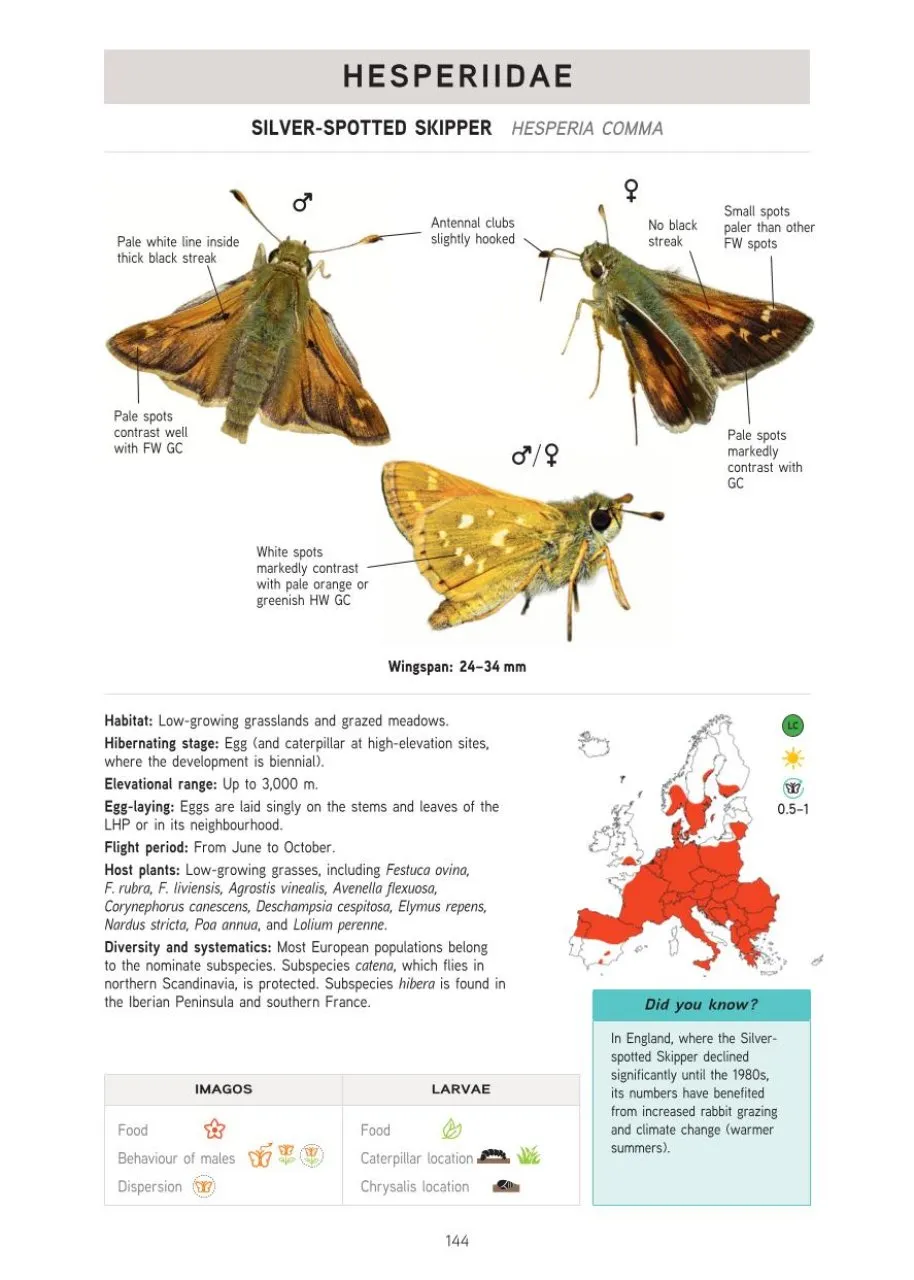

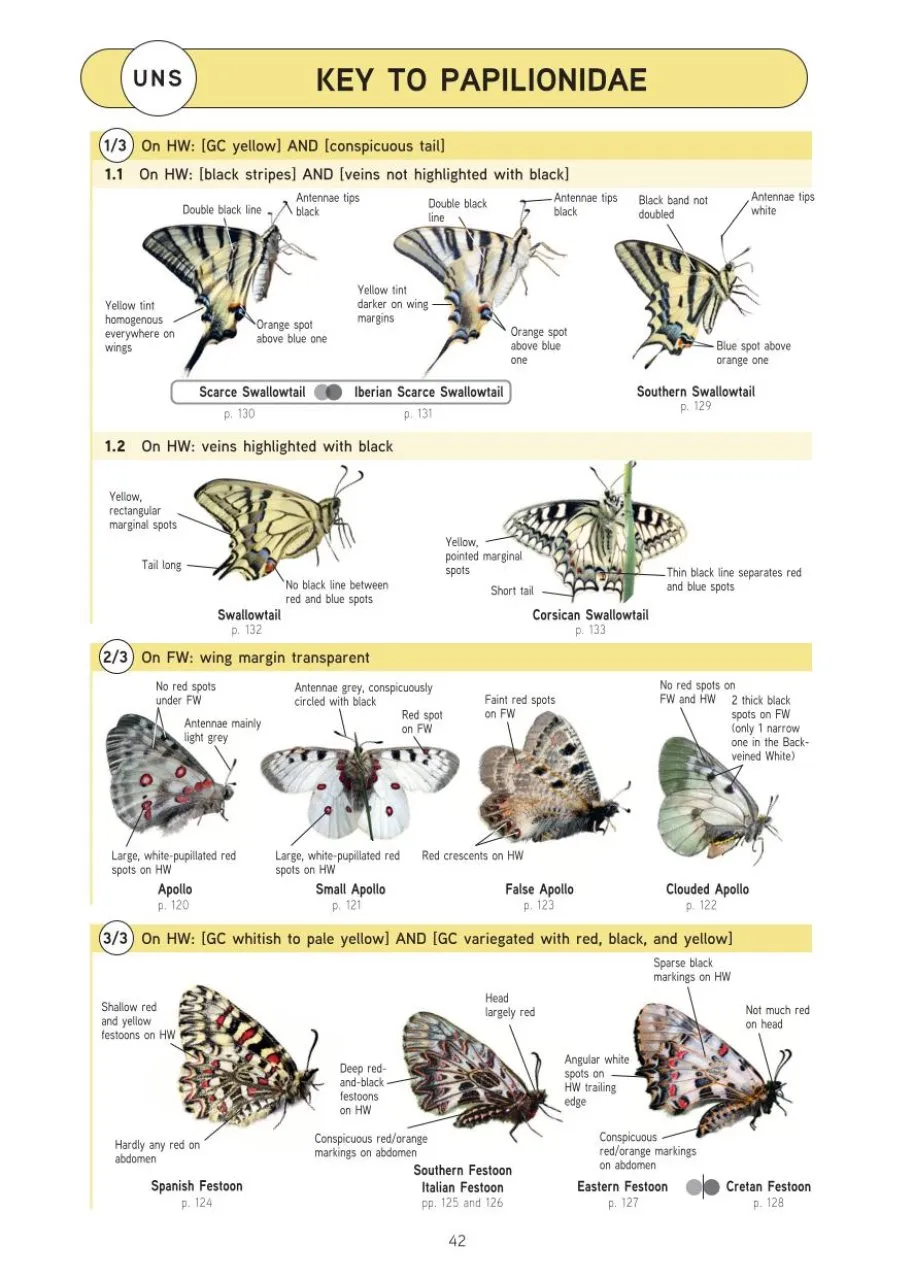

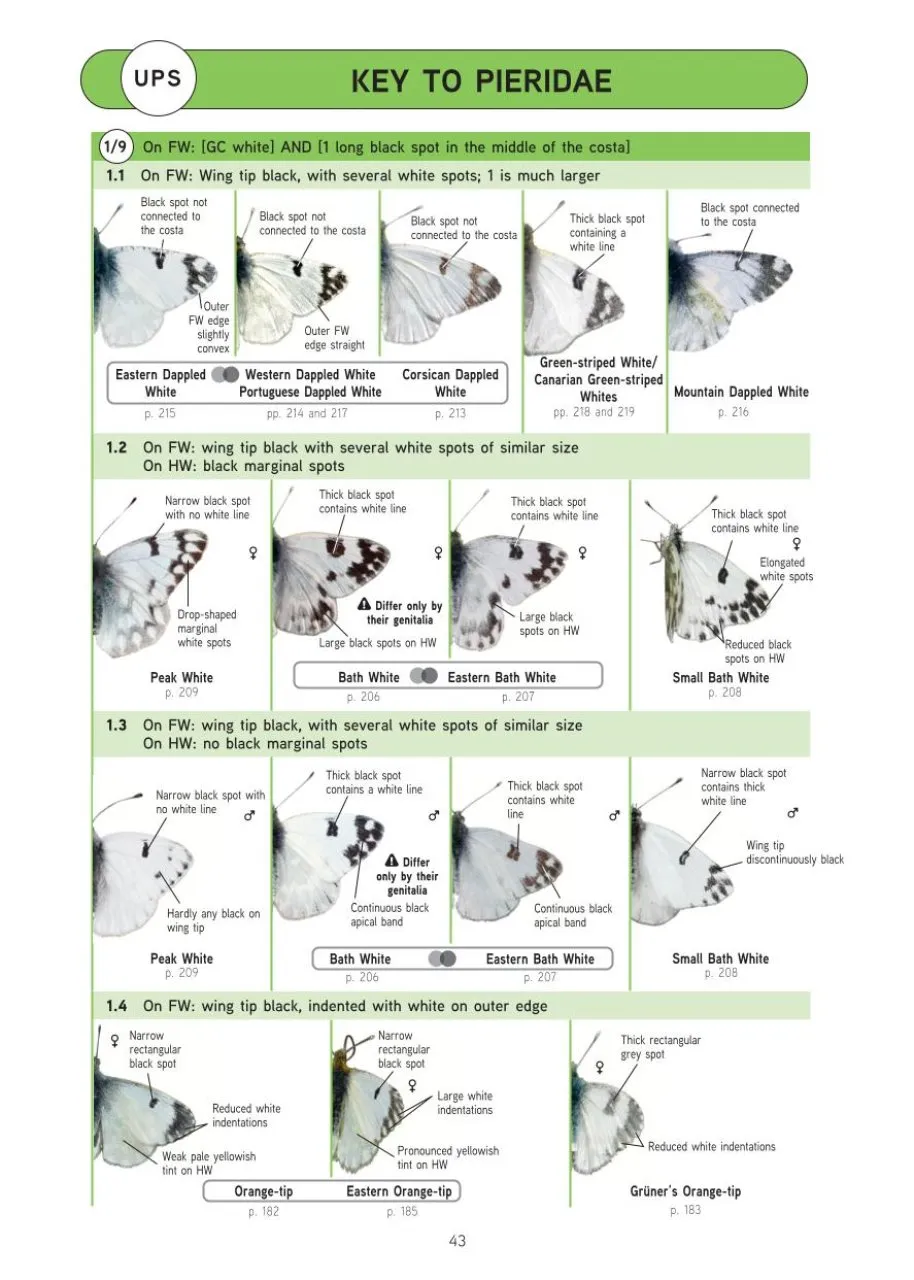

Keys to identification

The keys begin by helping the reader to place a butterfly seen into the appropriate family and then, for each family, further keys are offered that should lead to the identification of the species. For some species, for example the ‘Grizzled Skipper’ group, correct identification depends on obtaining good views of both the upper and underside of the butterfly and, where this is the case, keys are provided to both. Having worked out from the keys which species you are looking at, you are then referred on to a monograph/species page covering each butterfly which provides more information on its range including a distribution map, a note on larval food-plants and flight period. This is something of a fail-safe mechanism and allows one to re-check features possibly missed at the initial stage, and also helps distinguish between species that are virtually identical but can be separated by their geographical range. Species such as the Scarce Swallowtail and the Iberian Scarce Swallowtail and the three species of Greenish Black-tip are good examples of this. The author recognises that there is a temptation to miss out on the keys altogether (some of us are, I admit, a little resistant to using them) and head straight for the monographs but he warns against falling into this trap, which he suggests will inevitably lead to mistakes. However, he accepts that experience will enable users to shortcut this process eventually, when they know which grouping of species the yet-to-be-identified butterfly belongs.

Species covered

The guide provides details of 474 species, a growing list resulting from taxonomic studies that have led to new species being described. Some are former sub-species that have been elevated to true species status so, for example, the Vosges Ringlet was formerly considered to be a sub-species of Yellow-spotted Ringlet, from which it can only be separated by examination of the genitalia. Much of this work has been very recent and is still contentious, with opinions differing over whether particular newly described butterflies can be really classed as separate species. My previous go-to book on European butterflies (Butterflies of Britain and Europe: A photographic guide by T. Haahtela et al, published in 2011) lists 444 species so, in just 15 years, we have added 30 species to the European list: that’s two a year! To take just one group, the Anomalous Blues have grown from two species in 2011 to eight now. As the author acknowledges, the definition of a species remains a matter of convention, even where it is scientifically argued, and there is no doubt that new work will lead to further revisions.

Study guide more than field guide

The book extends to 640 pages and is a weighty tome in every sense of the word. It strikes me as less a field guide and more a book to be studied alongside one’s photographs (upper and lower sides where possible) on return from a European trip or perhaps back in the hotel room after a day in the field. Similar species are grouped together in the monograph section which is helpful and, to save space, a series of symbols are used to provide information about the number of generations, feeding and territorial behaviours, dispersal abilities, caterpillar feeding habits, location of caterpillars and pupae, and even the threat caused by climate change. I feel this is less successful: some of the symbols used are not very intuitive, although no doubt they'd become familiar with use and a fold-out section of the back cover explains them. In this regard, perhaps the author has been over-ambitious, including more information than is needed for identification and over-generalising other aspects of the life history. The monograph on the Brown Hairstreak, for example, lists 16 possible larval food-plants including interestingly hawthorn and even birch, which is not used in the UK to my knowledge.

A few reservations

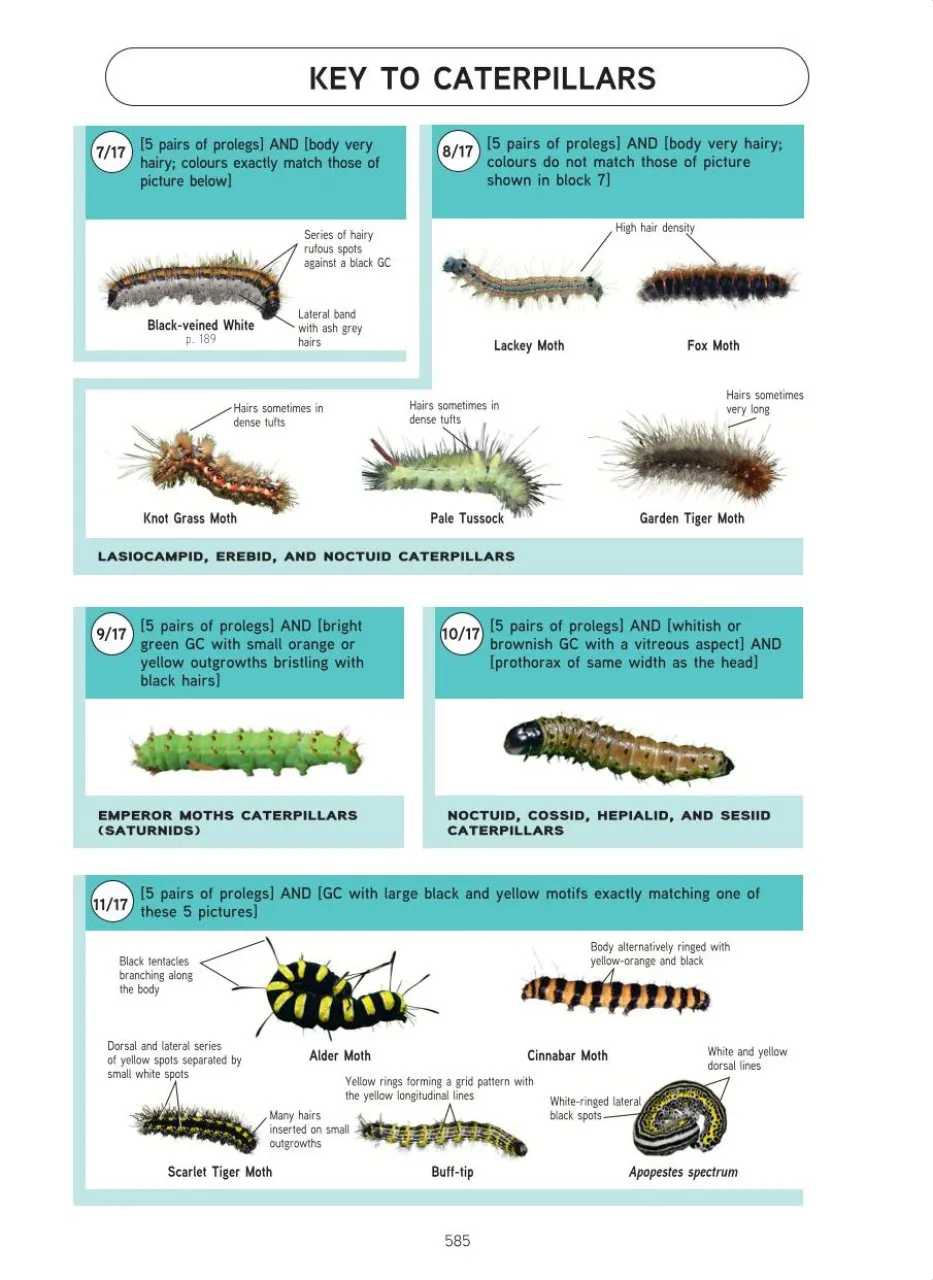

The inclusion of the sections on genitalia and caterpillars in a guide of this nature is certainly an innovation but one that I suspect will be used less by the average reader. Examining genitalia involves more handling of a butterfly than many will feel comfortable with and, in some cases, means killing the specimen, while the problem with caterpillars is, of course, that many will be moths or other insect orders not covered by this guide. The section does offer some assistance in identifying non-butterfly caterpillars which is helpful but still leaves many problems of identification with so many species having very similar caterpillars. The book only shows the final instar of each caterpillar’s life before it pupates, on the basis this is the stage most likely to be encountered which I am not sure is entirely true. The guide concludes with a very useful bibliography and list of useful websites. An index of English names with space to add the date and place seen will appeal to the butterfly twitchers amongst us. There are also some familiar names amongst the acknowledgements to those who supplied photos including Roger Wasley, who contributed so many excellent images to Butterflies of the West Midlands.

Conclusion

Despite these reservations, this is a tour de force among butterfly ID guides and the author is to be commended for completing such a comprehensive guide, justifying its claim to be 'an essential guide for all lepidopterists and entomologists from amateur enthusiasts to professionals'. Even if it is not suitable to be taken into the field because of its sheer size and weight (3lb 11oz), it is a very worthwhile purchase as a back-up to more portable guide books and enables many more species to be confidently identified. Priced at less than £30, it represents extremely good value for money.